It was hardly surprising that the UK economy contracted by 0.2% in the third quarter this year, given the dismal backdrop. High and entrenched inflation that arose from pandemic-induced dislocations was amplified by Putin’s weaponization of energy and delivered an economic shock across the globe.

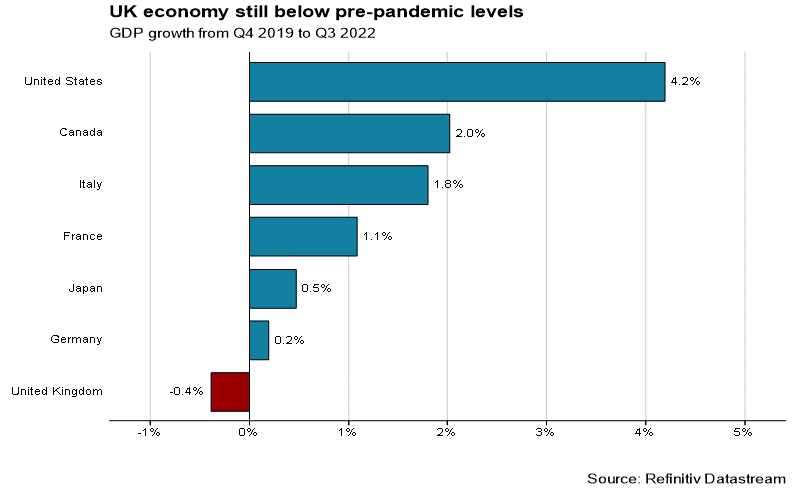

However, this contraction in economic growth, when viewed in a broader context, appears somewhat more concerning. Not only is the UK the only G7 economy to have contracted in the third quarter, but it is also the only major economy that has not recovered to its pre-pandemic output. What is responsible for the UK’s current demise and why does it find itself in a spot of bother?

Despite the achievements of the vaccine rollout and a quicker unwinding of lockdowns, the UK's economic performance has stagnated of late. Global challenges have, to some extent, had more of an impact on the UK than others. While the UK is less reliant on Russian gas, which only accounted for 4% of gas imports in 2021, it is more dependent on globally imported gas which makes up around 40% of its energy consumption. As global gas prices spiked in the wake of Putin's invasion of Ukraine, the UK economy was particularly badly affected.

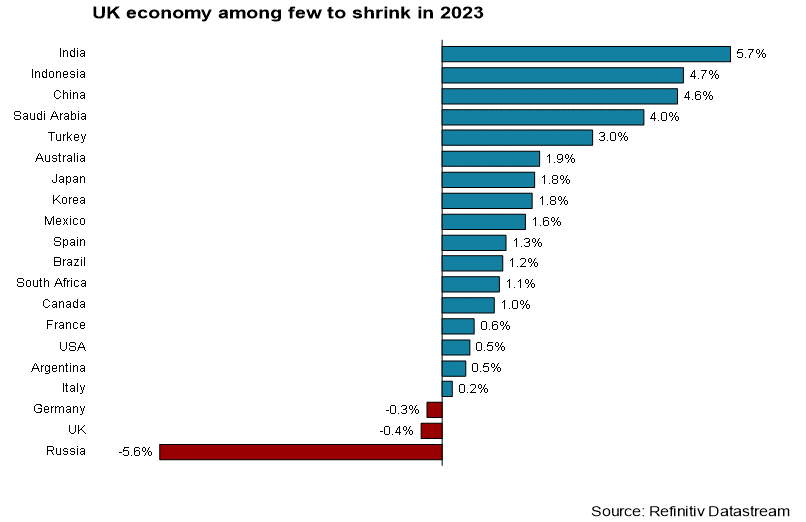

The weakness in sterling that has exacerbated inflationary woes has largely been a function of a strengthening US dollar rather than a reflection of the UK's economic performance. That said, the fall in the currency was compounded by the “mini-budget” under the Truss government, before the incumbent government reversed most of the policies. This aside, there are clear reasons for the UK's current troubles and why the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) predicts the UK will be the G20's worse performing economy, bar Russia, in the next 2 years.

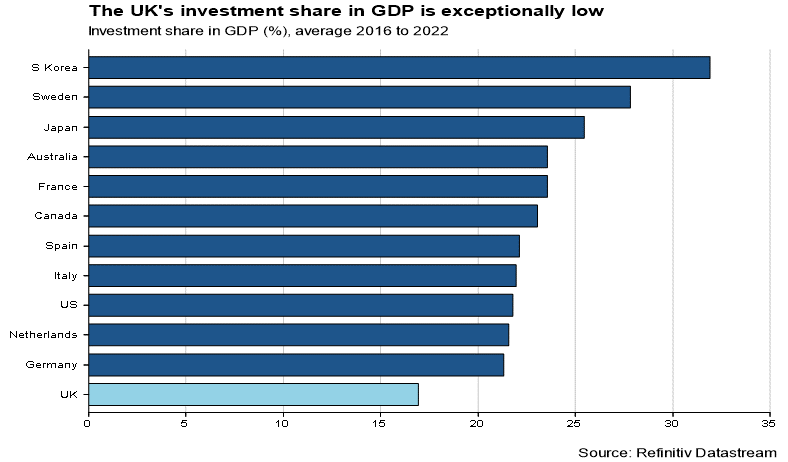

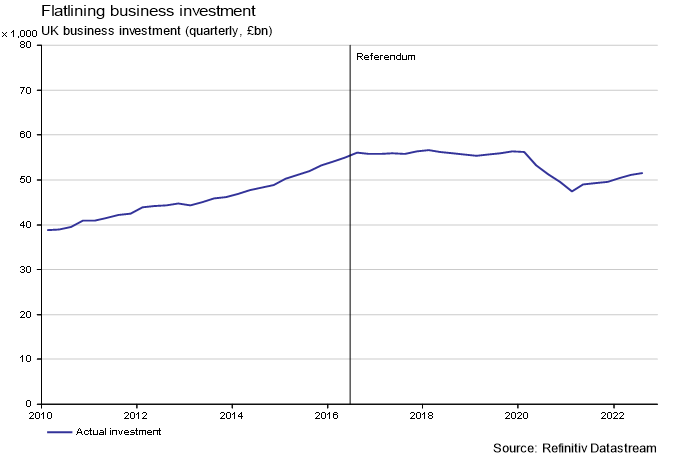

Amongst these factors are a decline in business investment post the 2016 referendum, structural issues with the labour force and weaker trade with the European Union (EU). Taking the former first, it is stark that UK business investment, as a percentage of GDP, has been significantly lagging many of its peers such as the United States and France since 2016. Furthermore, the nominal amount invested remains 6% below 2016 levels, declining of late following a couple years of flatlining.

The uncertain business and political environment that has encumbered the UK since the Brexit vote has driven up the minimum required return that investors demand on their investment – something referred to as the cost of capital. The effect of a relatively higher cost of capital has been to lower valuations compared to the rest of the world, while also reducing public and private market activity.

France’s stock market is now more valuable than the UK stock market All Share and, at the time of writing, UK equity funds have seen outflows of €22bn this year, compared with €2bn in France. The London initial public offering (IPO) market is also experiencing its quietest year since the financial crisis, as companies seek listings in other markets such as New York and Amsterdam.

Government finances also remain impacted by these higher borrowing costs, which was never more evident than in the wake of the “mini-budget.” While Rishi Sunak and Jeremy Hunt have sought to appease investors with a more fiscally responsible budget to help re-anchor borrowing costs, the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) still estimates the cost of servicing the UK's debt will rise to £83bn next year, equivalent to 5.2% of total public spending.

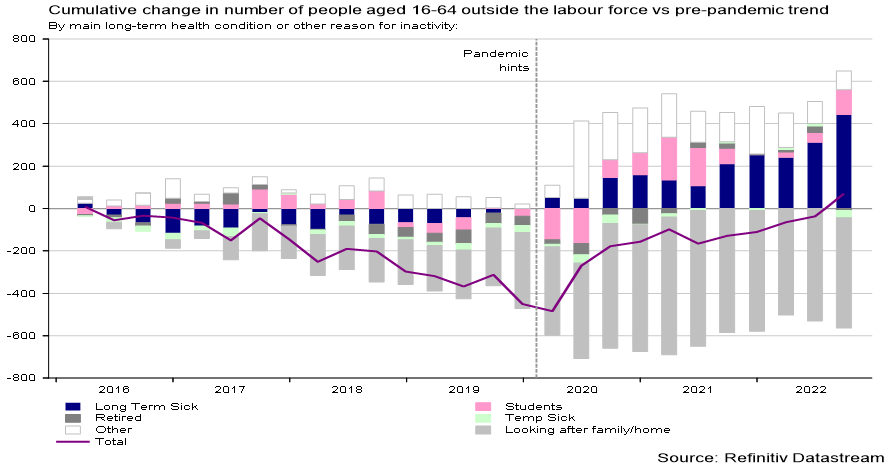

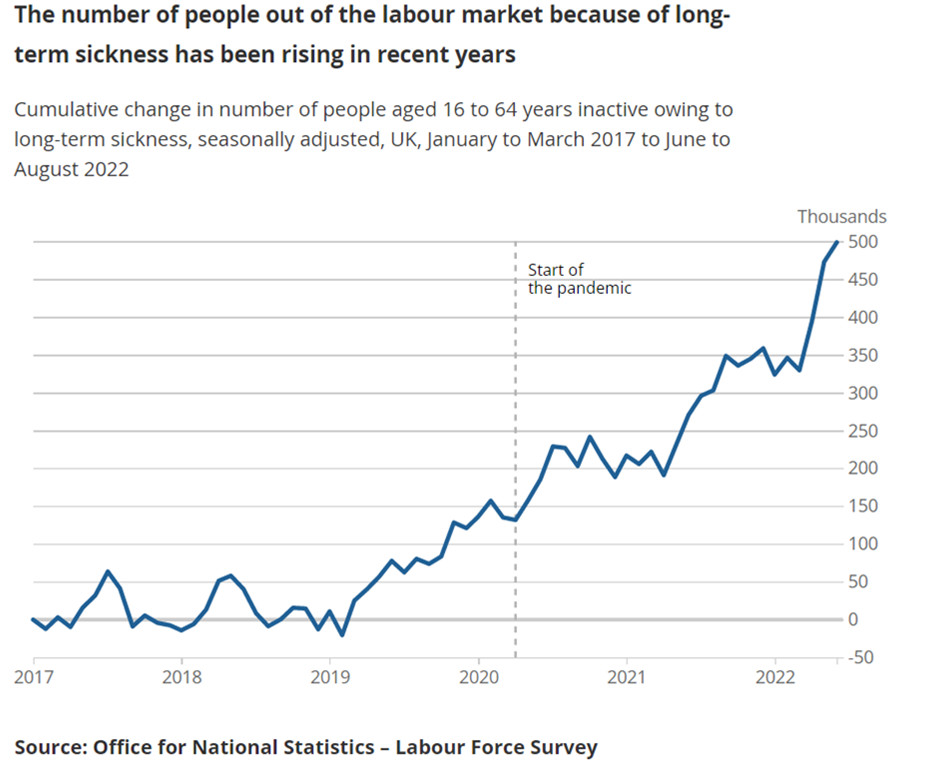

UK growth prospects are further inhibited by structural issues in the labour force. At present, the workforce remains over half a million below its pre-Covid levels despite the number of vacancies in the economy, at times, outnumbering the number of unemployed by two to one. While an element of this can be explained by a higher-than-average proportion of workers over 50 retiring early, the main problem lies with the health of the population.

The proportion of the working age population reporting long-term sick has risen to around 7 million people - roughly one in six - having stood at a little over 5 million in 2010. The figures are primarily a reflection of deteriorating mental health and cardiovascular illness. These adverse health trends are not only reducing the supply of labour but also suppressing UK productivity, as poor physical and mental health impacts workplace efficiency. The twin pillars of an improving and growing workforce that drove the unprecedented rise in living standards throughout the 20th century now appear to be reversing.

A final point to highlight is the UK’s weaker trade with the EU, electing as it did to erect trade barriers with our largest trading partners, in the wake of the Brexit Treaty. Last month the OBR noted “the latest evidence suggests that Brexit has had a significant adverse impact on UK trade” as overall trade volumes have fallen, as well as the number of trading relationships between UK and EU firms. According to OBR estimates “Brexit will result in the UK's trade intensity being 15% lower in the long run than if the UK had remained in the EU.”

The sustained fall in the pound is only adding to the conundrum as it makes the UK economic output less valuable in constant currency terms and amplifies imported inflation. With the current account deficit, that is where the total level of imports exceeds that of exports, accounting for 5.5% of GDP, the negative effects of the currency depreciation are outweighing any trading competitiveness a weaker pound offers.

For a turnaround to be achieved and for deeply unloved UK assets to rerate, the government must provide solutions to these challenges. While an innovative growth plan or supply side reforms could be useful, tackling the backlog in the NHS to help get people back to work is a more immediate concern. To give businesses the confidence to invest again the government needs to offer a more stable political environment. But most importantly the government need to acknowledge the largely non-contentious economic evaluation, rather than ignoring it and hiding behind Brexit intransigence. Ministers do not look like serious people if they deny what capital allocators can see in plain sight. An acknowledgement of the difficulties and visible steps taken to address them would encourage investors to return to the market.